Photogrammetry is a technique which uses a series of 2D images of an artefact, building or landscape to calculate its 3D measurements. In the past it was done manually, but nowadays it involves feeding a number of 2D photographs of the subject, taken from different perspectives, into specialist software, which uses them to construct a digital 3D representation.

The digital 3D model may then be manipulated on a screen to show different angles, viewed in virtual reality or as a “fly-through” video, or printed using a 3D printer. It may be useful for study in research, teaching or to ensure preservation of the original.

Compared to other methods of 3D digitisation, photogrammetry is inexpensive, requiring, at the most basic level, only a camera and access to the relevant software program. It is particularly suitable for projects where a photorealistic model is needed.

This blog post recounts the experiences of a non-technically minded beginner in making two 3D digital models and hopefully illustrates that anyone can carry out a basic 3D digitisation project with only a little help.

For a first attempt at photogrammetry, an object that would be straightforward to digitise was needed. A plaster bust from the University of Bristol Library’s Special Collections department was suitable, since its matt surface would not reflect light, which can create problems when building the 3D model. Also, being mounted on a plinth would make it possible to take photographs from all perspectives without having to turn over the object.

The second object was chosen because it was particularly fragile and in need of a digital surrogate that people could study in order to minimise handling of the original. It was, unusually, a piece of toast, held by the University of Bristol’s Theatre Collection, which originated as a piece of publicity by Julie Flowers and Rosalind Howell for a live art performance entitled ‘Grill… A piece of toast’ at the National Review of Live Art 1994 Platform.

It is preferable to have even, natural lighting over the object to be photographed. Outdoors on a cloudy day would probably be the ideal situation, but indoor photogrammetry will normally be necessary when dealing with artefacts from the archives. It is best to avoid flash. In digitising the plaster bust and the toast, two lights were positioned to reflect off the white ceiling, to minimise shadows. LED lamps are best, when dealing with sensitive items, for purposes of preservation.

A turntable can be used to rotate the object while keeping the camera in a stationary position, but it is also possible to move with the camera around a stationary object if a turntable is not available.

Photographs should be taken from several levels with, roughly, a 30% to 50% overlap between images. The idea is to get coverage of all surfaces of the object, with enough overlap between the individual photographs to allow the software to identify common points and match up the images. Any part of the object not captured in a photograph will appear as a hole in the finished 3D model, so it is important to photograph any obscured parts of the object, for example up the nose or under the chin of the plaster bust.

The toast, having two sides, needed to be turned over (very gingerly, by the Archivist) and the process repeated with the second side. People have tried other solutions for capturing all surfaces of an object, such as finding ingenious ways to balance or suspend it, or placing it on a transparent surface, but these methods are not without problems (especially for a fragile object) so it seemed best to capture the two sides of the toast separately and rely on the software finding enough common points on the toast edges to match the two sides correctly.

The software used to process the photographs into a digital model was Agisoft Photoscan, which is straightforward for beginners to use as it has a workflow, beginning with adding the photographs and directing the user through the different stages of the process.

Once the photographs are added, Photoscan aligns the images by comparing the different viewpoints of the photographs and builds a sparse point cloud, which is a raw 3D model made of points but no edges. This can be tidied up, if wished, before building a dense point cloud. Depending on the number of images and capability of the computer, a significant amount of processing time may be needed.

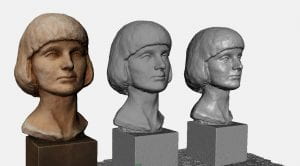

The next stage is to build a mesh, which is a polygonal model, based on the point cloud data, so a bit like joining the dots of the point cloud. The final step adds the coloured textures that wrap around the model so that it looks realistic.

The 3D model of the plaster bust came out well first time, but it took several attempts for Photoscan to fit together the two sides of the toast. The best method turned out to be to process the photographs in two batches, one for each side of the toast, and then to match the two sides together by marking the same identifiable point on the edges of each half, so that Photoscan could correctly align the two halves into one 3D whole. In addition, the background, on which the toast had lain, needed to be manually edited out, as Photoscan had not recognised that this was not part of the object, which had happened automatically with the bust.

The 3D model can then be exported and three files will be generated: an .obj file containing the 3D geometry; a .png or.jpg file containing the colour and texture information; and the colour placement information (.mtl) which provides co-ordinates to map the colour and texture on to the geometry.

The final model can be viewed in Windows 3D Viewer, or uploaded to an online platform for sharing, such as Sketchfab.

The Library Research Support team runs courses on 3D digitisation, which concentrate on photogrammetry, but also touch on structured light scanning. The team also has a selection of equipment, including cameras, scanners and a PC with the Agisoft Photoscan software, which can be booked and used by University of Bristol researchers. You can find out more on our digital humanities webpages.