The Uncertain Space is the new virtual museum for the University of Bristol. It is the result of a joint project between Library Research Support and Cultural Collections, funded by the AHRC through the Capability for Collections Impact Funding, which also helped fund the first exhibition.

The project originated in a desire to widen the audience to some of the University’s collections, but in a sustainable way which would persist beyond the end of the project. Consequently, The Uncertain Space is a permanent museum space with a rolling programme of exhibitions and a governance structure, just like a physical museum.

The project had two main outcomes: the first was the virtual museum space and the second was the first exhibition to be hosted in the museum. The exhibition, Secret Gardens, was co-curated with a group of young Bristolians, aged 11-18 and explores connections between the University’s public artworks and some of the objects held in our rich collections.

The group of young people attended a series of in-person and online workshops to discover their shared interests and develop the exhibition. The themes of identity, activism and environmental awareness came through strongly and these helped to inform their choice of items for the exhibition.

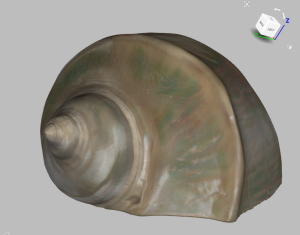

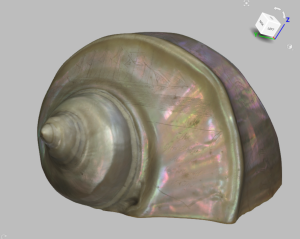

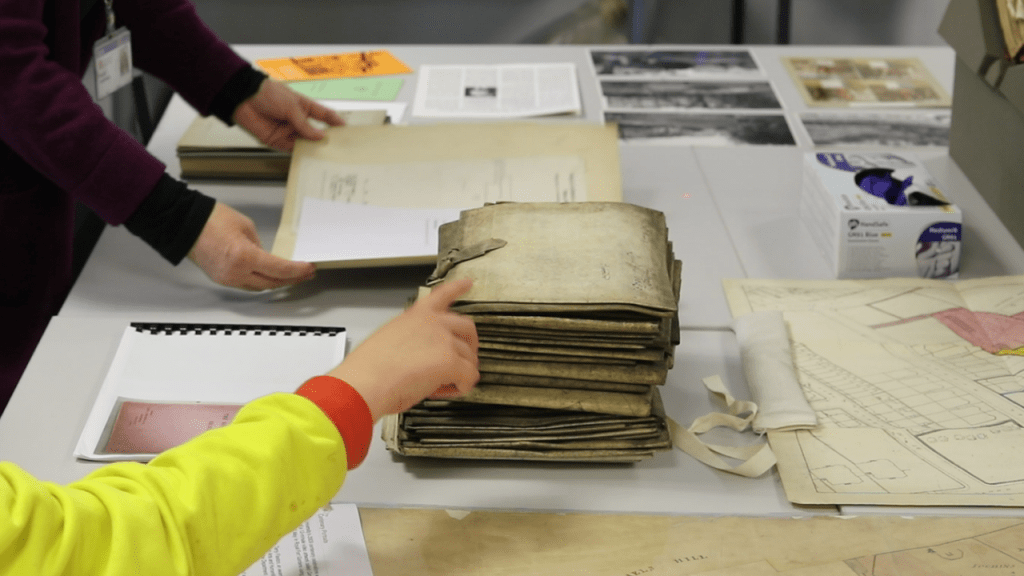

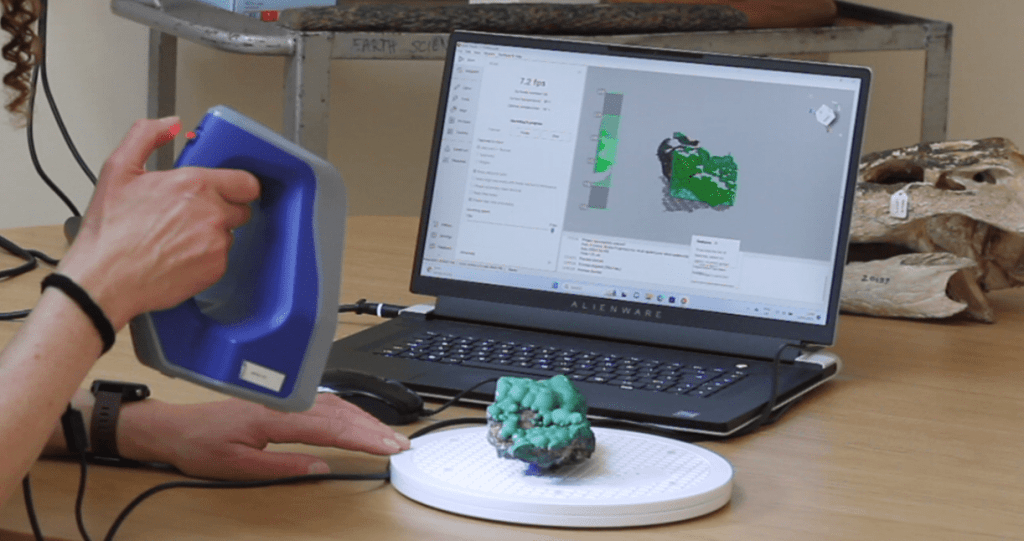

Objects, images and audiovisual clips, to link with each of the public artworks, were selected from the Theatre Collection, Special Collections, the Botanic Gardens and from collections held in the Anatomy, Archaeology and Earth Sciences departments. For some of the choices, digital copies already existed, but most of the items had to be digitised by photography or by scanning, using a handheld structured light scanner. The nine public artworks were captured by 360 degree photography. In addition, the reactions of the young people were recorded as they visited each of the public artworks and these are also included in the exhibition.

As the virtual museum was designed to mimic a real-world exhibition, the University of Bristol team and the young people worked with a real-world exhibition designer, and it was found that designing a virtual exhibition was a similar process to designing a real-world exhibition. Some aspects of the process, however, were unique to creating a virtual exhibition, such as the challenges of making digital versions of some objects. The virtual museum also provides possibilities that the real-world version cannot, for example the opportunity to pick up and handle objects and to be transported to different locations.

Towards the end of the project, a second group of young people, who were studying a digital music course at Creative Youth Network, visited the virtual museum in its test phase and created their own pieces of music in response. Some of these are included in a video about the making of the museum.

The museum and first exhibition can be visited on a laptop, PC or mobile device via The Uncertain Space webpage, by downloading the spatial.io app onto a phone or VR headset, or by booking a visit to the Theatre Collection or Special Collections, where VR headsets are available for anyone to view the exhibition.

We are looking forward to a programme of different exhibitions to be hosted in The Uncertain Space and are interested in hearing from anyone who would like to put on a show.

You can read more about the making of The Uncertain Space and its first exhibition from our colleagues in Special Collections and Theatre Collection:

Our collections go virtual!

Digitising for the new virtual museum: The Uncertain Space