Notes from the Discovering Collections, Discovering Communities (DCDC19) conference, organised by The National Archives, RLUK and JISC, which took place 12th-14th November 2019, in Birmingham.

The theme of DCDC19 was billed as ‘navigating the digital shift’. As the conference progressed, however, unofficial themes soon emerged. On the first day of presentations (officially day 2 of the conference) it became apparent that the conference would be as much about ‘collaboration, consultation and communication’ as about the digital dimension. The scale of the digital endeavour means that these three aspects are essential to achieving digital projects that are relevant for their intended audiences. A second thematic strand around ideas of truth, misinformation, accurate representation, marginalisation and bias ran through many of the papers, as speakers questioned how well the Gallery, Library, Archive and Museum (GLAM) sectors represent communities or historical events, and examined issues of authenticity in the digital dimension. The first afternoon and evening were occupied with preconference events and the main business of the conference took place on days two and three, with keynotes plus a variety of panel session papers and workshops running in parallel.

Opening Keynote: Tonya Nelson, Director of Arts Technology and Innovation, Arts Council England

Tonya Nelson, giving the opening keynote, was the first of several speakers to consider the possibilities for representation of a wider range of perspectives in the digital world and the challenges and opportunities of the digital environment. She examined three key issues in the digital shift:

- Making sense of information Tonya asked how we can help people make sense of the vast range of information available and gave examples of different ways this may be done.

- Historical data may be used to make sense of current phenomena, as in Anna Ridler’s Mosaic Virus , a video work generated by artificial intelligence, which links the “tulip-mania” of the 1630s to current bitcoin speculation.

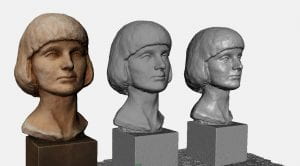

- Data may be visualised in new ways, such as the digital sculpture by Refik Anadol, Black Sea: Data Sculpture, based on high frequency radar collections of the Black Sea.

- Immersive technology may be used to give a sense of the world around us, as in Resurrecting the Sublime, a digital art project recreating the smell of extinct plants in a herbarium collection, using DNA.

- Transforming information into power Tonya asked how we can help our audiences transform information into power so it can change their communities. Examples of this were:

- Cleveland Museum of Art, which has made its collections open access and is encouraging people to remix and use them in interesting ways.

- The British Library’s Imaginary Cities exhibition, which used the digital map archives to create new fictional cityscapes.

- The Justice Syndicate, an immersive performance exploring how we navigate through information and misinformation, in which the audience act as a courtroom jury in a murder trial and are periodically fed information according to how they interact with the system.

- Supporting new forms of authorship Tonya considered how we can support new forms of authorship, particularly from underrepresented communities, and grapple with issues of authorship, ownership and artificial intelligence (AI) biases in the digital age? For instance:

- Some marginalised authors self-publish poetry on Instagram, leading to the challenge of capturing and archiving material published on social media

- Choreographer Wayne MacGregor’s Living Archive, used his extensive video archive to train AI to choreograph new dances, raising questions around authorship and the transparency of the training which underlies machine learning.

- Machine learning bias was uncovered in a project aiming to identify black people in old master paintings, when machine recognition was unable to detect the black face in Manet’s Olympia, thereby further marginalising the minority figure. Machine learning needs to be inclusive.

In the question and answer session, Tonya discussed the need for organisations to identify which skills need development and announced the launch of a tool to help organisations benchmark their digital capability and make plans for improvement. The Arts Council also have Tech Champions to provide support. Tonya highlighted the need to consider the relationship with the audience for digital productions. As a good example of where wellbeing and the intersection between technology, art and health has been thought about, she cited Marshmallow Laser Feast’s We Live in an Ocean of Air, a virtual forest that monitors the participant’s body so they can see their breath and pulse. Tonya asked whether we are doing enough to draw in influences from the wider world? The Arts Council are working on the relationship between the tech sector and the cultural world. Other challenges were considered such as a lack of flexibility to act for archives in organisations that don’t have an interest in the forward-looking use of their services; upskilling the leadership and the need to meet the core remit. Key messages to take away were the importance of communication with intended audiences, collaboration with colleagues and fostering an innovation mindset in order to evolve from repositories to information laboratories and data activists.

Developing digital platforms

The panel sessions all comprised three papers, followed by questions and answers. The Developing Digital Platforms session was chaired by Chris Day of The National Archives.

Eating the elephant: tackling the Express & Star photograph archive one bite at a time

Scott Knight (University of Wolverhampton) and Holly McIntosh (Wolverhampton City Archives) described a partnership between their institutions and the Express & Star newspaper to digitise, catalogue, preserve and make available a photograph archive of 20th century life in the West Midlands. Having a Heritage Lottery Fund development grant to digitise the photographs meant that they had the help of an HLF mentor to understand the challenges of large-scale digitisation and of copyright issues. Public engagement and consultation were a significant element of the project and brought wonderful stories into the archive. Social media was used, which helped to identify locations and to connect people with the photographs and with long-lost relatives, and the project was also promoted through the Express & Star and on local television news. There was no dedicated project manager or team, but there were volunteers. This brought challenges of managing expectations, but a lot of sorting and tidying occurred as an additional benefit. The project is ongoing and now funded by local organisations.

The GDD network: towards a global dataset of digitised texts

Paul Gooding (University of Glasgow) described the AHRC-funded, Global Digitised Dataset Network, led by the University of Glasgow. It aims to address the feasibility of a global dataset of digitised texts and is working primarily with monographs. The key issue is that although much digitised text exists, there has been a lack of co-ordination at national and international level, which leads to fragmentation and problems of discovery. Paul outlined some of the context in which the network was working, such as a lack of supporting infrastructure to allow collaboration; the shift towards mass digitisation; and the growth of data-driven research. There was a need to move away from the idea of ownership and to balance the involvement and agendas of partners in the network. Paul also considered what global means, for example linguistic, cultural and technological inclusion, and how this relates to the remit and holdings of the national libraries. Discovery, access, and efficiency are priorities. Consistency would also be a benefit of a global dataset, for example having one first edition for referencing would be useful. However, the network found problems matching data between catalogues, so that detecting duplicates internationally will be difficult. A prototype dataset and report are expected in December 2019.

Manchester Digital Collections

Ian Gifford and John Hodgson (Manchester University) introduced Manchester Digital Collections, an enhanced version of the image viewer developed by Cambridge University, enabling viewing of high quality digital images, with the ability to zoom in on fine detail, download, or share on social media. The project involved collaboration between academics and cultural institutions at Manchester, as well as with Cambridge University colleagues, which brought a range of challenges and learning experiences. The different organisational structures and cultures (autonomous and devolved versus more centralised, technology driven versus researcher driven, risk taking versus risk averse) meant a risk of communication failure. This was addressed by a project board bringing together stakeholders to learn from each other. Another challenge was the difference in technical approach. Cambridge have a dedicated digital library team and use the cloud for hosting, while at Manchester, the Library team had to upskill themselves and take the lead, collaborating with their central IT department over local hosting. The benefit was a new co-operative relationship between the library team and IT services. Unlike Cambridge, whose digital content tended to be developed via funded projects, Manchester had to import a wide range of legacy data in various formats from various sources, which could not be achieved via an automated process, so much effort was required to transfer the content. Manchester are reviewing processes and training staff in order to standardise data more in future. Future directions include working on public engagement, moving towards an open source model, online exhibitions, and prioritising researcher requirements. In keeping with the unofficial conference themes, lots of the lessons learned were about the importance of communications and collegial working. It is hoped to eventually widen the partnership to other institutions.

Questions to the panel

The panel was asked about the sustainability of projects. It was felt that impact is important and there is a need to keep returning to the audience to make sure the project serving their needs and to see how the resource can be used in different ways for other activities and applications. There should be engagement with other projects to avoid replication. The panel discussed behaviours for effective collaborations and suggested these were transparency, understanding internal drivers, building a close relationship, not assuming goals or wishes, questioning assumptions about how things should be done, meeting face to face and mutually respecting expertise and differences. There was also discussion on dealing with anomalies in digital collections or catalogues. It is not possible to achieve perfection, but the audience can help point out deficiencies. It is important to use health warnings and to try to debias and be aware of worldwide audiences.

Keynote: Navigating the Digital Shift: Partnerships in Practice Liz Jolly, Chief Librarian, The British Library

Liz Jolly explained how the British Library’s strategy document ‘Living Knowledge’ encompasses the idea of making heritage accessible to everyone for research and also for inspiration and enjoyment, before going on the discuss its six purposes: custodianship, research, business, culture, learning and work with international partners. Her talk focused on the themes of partnership and engagement, openness and accessibility of spaces and information, and on diversity and inclusion. Examples given of partnerships were:

- Business and IP centre National Network, in partnership with public libraries, which supports entrepreneurs across the UK to help start, protect and grow businesses. There is evidence that this is supporting diverse groups and being very effective in terms of return on public money invested.

- Living Knowledge Network, a collaboration with national and public libraries to exchange knowledge and develop experiences for users.

- Single Digital Presence report, which investigates what a national online platform for public libraries might look like. A single digital presence could mean different things: a deep shared infrastructure or single Library Management System for the country; UK-wide content discovery; unified digital lending; a social space; or a single library brand for public libraries, which would make it easier to advocate for public libraries.

- UK Research Reserve, which partners with academic libraries in a space-saving exercise to deduplicate journal holdings around the UK.

- The UK web archive, collecting digital publications and also material on the web.

- The Living with Machines project, in partnership with the Alan Turing Institute, using big data for digital humanities research on the impact of technology on people’s lives during the Industrial Revolution.

Liz reflected that the benefits of working in partnership include learning from other organisations. She stressed that many of the elements of working successfully in the digital world are the human elements and we need to put co-creation of services at the forefront of what we do. Liz also focused on the importance of diversity and inclusion in partnering with our communities, pointing out that a CILIP workforce survey showed 97% or workers in the information sector identify as ‘white’ and 79% are female, though males in the sector are twice as likely to get a top job. Lessons learned included: the need to listen to our communities; the need to share our professional knowledge; that digital literacy needs to be bespoke, i.e. people need to be digitally literate in ways relevant to their work; becoming a reflective practitioner is important. The keynote ended by emphasising the importance of working together with communities to become more effective partners in the digital world. During the question and answer session, Liz explained that engaging minorities successfully is about going out and building relationships with people and also making spaces inviting and not intimidating. Liz spoke about dismantling barriers for entry to the profession, suggesting that perhaps the profession had focused too much on one method of entry and there should be multiple ways in that are different. Liz described libraries as constructed around 3 elements: content, space, and staff, with community being placed in the centre, but pointed out that it is the librarians who make the space a library.

The digital workforce: navigating the skills shift.

This panel session, chaired by Elizabeth Oxborrow-Cowan, aimed to explore how organisations are navigating the shift in skills, practices and professional culture in the digital age.

The everyday (digital) archivist

Jo Pugh (The National Archives) introduced the digital capacity building strategy Plugged In, Powered Up, with a focus on engagement, access and preservation, which are all key in increasing access to collections. Jo suggested organisations might approach digital engagement in different ways, such as using social media to tell stories, wikithons or engagement through Minecraft. As part of the strategy, digital engagement grants are offered to organisations interested in working participatively with audiences (deadline for applications January 2020). Jo referred to a survey, carried out with JISC earlier in 2019, which showed only 1 in 3 archivists feel they have the digital skills they need. The work being done by the National Archives on digital engagement includes

- Working on a pilot to crowdsource cataloguing

- Guidance on how to do research with digital collections

- ‘Novice to Ninja’ digital preservation guidance

- A taught course at TNA, ‘Archives School’, covering the practical skills of delivering digital preservation

- Development of a digital leadership programme

- DALE, the Digital Archives Learning Exchange, a network for archivists involved in digital work

- Looking at alternative routes into the sector as current archival courses don’t equip people with the digital skills they need

Jo concluded by stating that archive professionals must continue to develop their skills as this is the biggest challenge facing the sector.

Keepers of manuscripts to content managers: navigating and developing the shift in archival skills

Rachel MacGregor (University of Warwick) looked at the hybrid environment in which archives are operating, which means that archivists need to keep their old skills as well as developing new ones to manage digital collections. Rachel outlined the barriers to developing new skills as time, resources, IT support, confidence and subject knowledge. The SCONUL report, Mapping the Future of Academic Libraries examined ways in which libraries could move into the digital sphere. Rachel said that archivists should stick to the values that define what they do and be open about practice, however in the digital realm, the pace of change is fast so it can be hard to get to grips with this practice. Rachel outlined some risks of not doing anything, including loss of reputation, inadequate resources and an inability to support users. Other challenges include descriptive standards, which may not be fit for purpose, and campaign for change is needed. Rachel acknowledged that digital collections can be difficult to make available as there are questions of copyright and data protection, but said that we should share good practice about how we make things available and how we present and promote collections. She felt that it is unrealistic to expect to always meet the gold standard, but better to do something rather than nothing.

Archives West Midlands: new skills for old? The shift from analogue to digital.

Joanna Terry (Staffordshire Archives & Heritage) and Mary Mackenzie (Shropshire Archives) spoke about Archives West Midlands, established in 2016 as a charitable organisation with 16 subscribed members across the West Midlands. They outlined how the member organisations harnessed the power of collaborative learning to establish ‘digital preservation readiness’ and then to establish policies and guidance for navigating the skills shift from analogue to digital. With the help of funding from TNA and Worcestershire Archives and Archaeology service, and using The National Digital Stewardship Alliance (NDSA) Levels of Digital Preservation, they surveyed the current situation and ongoing requirements, identifying technical gaps, limiting factors and priorities for development. They followed this with practical work. Workshops were delivered looking at Preservica and Archivematica, they engaged with IT services at a regional level and also developed documents, such as a digital preservation template, guidance for depositors and a business case that other archives can adapt and use. The last stage of the project was a knowledge exchange with another similar project.

Questions to the panel

The panel gave suggestions for getting started on the digital route, including taking stock at one’s own organisation to see what needs to be done, using free tools, finding something small to start with and talking to another archivist. The main message was just to have a go. There was also discussion of ways into the ‘Archives School’ course and it was emphasised that there should be different routes in, but that everyone is working together.

Value and the Digital Archive

Neil Grindley of Jisc chaired a panel session exploring how we assign value to archives and what competing notions of value mean in the digital space.

The end of value? Digital archives as cultural property

James Travers (The National Archives) shared the initial findings of his research into perceptions of the value of digital archives and asked whether the digital shift is a challenge to the view of archives as cultural property. He asked whether digital archives have the same financial, evidential, iconic, magical and social benefit as physical archives. Though the evidential value should, in theory, be the same for digital as for other archives, his research suggests that this might not be the case. James suggested a range of possible digital futures

- The current mechanisms cope with digital archives

- There are minor gaps in knowledge and skills that can be mitigated

- Digital archives present a radical challenge and radical change is needed

- New mechanisms are required to maintain archives as cultural property

- Archives lose their status as cultural property and will need to seek funding from other sources.

The current hybrid collecting pattern will reach a tipping point where archives will become predominantly digital. Will these digital archives have less financial value? James concluded that despite the lack of a market currently, digital archives will maintain their value, but the rights may transfer from owner to institution.

Can digital archives be emotive? Developing a digital platform for the Manchester Together archive

Jenny Marsden (Manchester Art Gallery) described a project to catalogue and digitise items from the Manchester Together Archive of tributes left by the public following the Manchester Arena attack in 2017. Jenny explained that visits to the physical archive space are often emotional and there may be therapeutic value for families in visiting. The reasons for digitising the archive mostly related to the sensitivities surrounding the archive, for instance some people don’t want to come to Manchester and some still treat the archive as a memorial, not wanting items to be handled. There are similar online memorials for the 9/11 attacks and the Boston Marathon bombing and these digital archives are often seen as living memorials. Part of the project involved identifying potential audiences and engaging people to discover opinions. It was found that people responded strongly to photos of the memorial and liked the organisation and order of the archive, interpreting it as showing care. It is intended that the platform will enable storytelling. One idea is to undertake oral history interviews and to crowdsource data from those who left an item and are willing to say why. There is also interest in the geography of the collection and the journeys that items in archive have made. There were difficult questions to tackle surrounding the sensitivity of the archive. Some visitors felt the material was too personal to put online and some children were worried about the lack of control of comments about items online. Jenny asked whether it is responsible to create heightened emotion when no-one is there to provide support and concluded that physical and online archives don’t do the same things.

Touching the past through ‘digital skin’: communicating the materiality of written heritage via social media.

Johanna Green (University of Glasgow) discussed the importance of the sensory experience for students studying medieval manuscripts and the fact that digital images fail to represent “the smell, the heft, the texture, the sound” of texts. Her talk explored the potential of social media to bridge this sensory gap. Johanna used an Instagram account, as Twitter is perceived by students as “for old people”, to post images she had taken herself, trying to show what it’s like to be in the reading room. The comments showed students engaging with the images. It was found that traditional images fail to engage senses other than sight, whereas scruffy or complex items seem to capture the audience’s imagination. Images or video clips portraying the codex as a complete object, e.g. showing pages being turned, were the most engaging. The inclusion of curatorial hands in the image communicates sensory information, such as size, or how the book is opened, and as a result, students develop a deeper understanding of how and why manuscripts are complex objects.

Questions to the panel

The panel was asked how well the idea of value is understood. They answered that it is necessary to adapt the way you talk to your audience. Also, that it is easier to advocate for a project if there is support from the audience. Value comes from the engagement, which can be cast in monetary terms, e.g. having attracted x number of students to a course. One questioner asked about the emotive experiences of staff working on the Manchester Together Archive project. Staff worked with the Manchester Resilience Hub (set up in response to the Manchester Arena attack) on how to support volunteers. Volunteers are warned that the material might be upsetting and receive a debrief at the end of each shift. The monetary cost of projects requiring technology was raised and it was pointed out that though there might be a point where the monetary cost outweighs the value of the objects, there will be social value that accrues. Johanna Green was asked how important is it for one’s personality to come across on social media? She replied that there is an expectation of the types of comments that will be provided with the images and decisions to be made about how much to reply to comments or add information. Replying to comments can be time-consuming and a social media account takes lots of work .

Keynote: A Reckoning in the Archives / America’s Scrapbook Lae’l Hughes-Watkins, University Archivist, University of Maryland

Lae’l Hughes-Watkins delivered an impassioned and well-received keynote, using a vision of “America’s scrapbook” to illustrate the erasure of minority communities from history. She challenged the archives sector to confront the colonial, racist, sexist and classist approaches of traditional archival practice. She recounted her own realisation as a student that black history is underdocumented in the archives and said she became an archivist because she wanted archives to represent the full breadth of human experience. Much of her work has involved liaising with individuals and communities to overcome the distrust of institutions. Lae’l described her work in capturing student activism on campus, which is not represented in the traditional media, but in social media posts. There are challenges in archiving this material fairly as it is fragmentary and can lack context. Lae’l observed that “we are still unpacking what it means to archive the Now”. The keynote concluded with a challenge to the profession to let go of ideas of neutrality and to move to “be more honest with who we have been and have hope for what we might become”. The discussion following the keynote returned to the idea of neutrality and the fact that the act of deciding what to keep in an archive is not a neutral act. It also focused on the importance of working with communities. Lae’l described working with student activists to make them part of the process of determining how they want to be represented and remembered. She also discussed the necessity of outreach and engagement to gain the trust of potential donors.

Digital transformation: organisations and practices

This panel session, chaired by Karen Colbron (Jisc), considered how the digital shift is transforming our organisations and relationships with our audiences.

Ask your users. Then ask them again: embedding user research in a big institution

Jenn Phillips-Bacher (Wellcome Collection) spoke about the Wellcome Collection’s approach to putting user research at the heart of product development. The Wellcome Collection had found that typical digital project culture, with tight budgets and timelines, temporary teams and outside IT expertise tended to result in a proliferation of separate websites and a disjointed user experience. At the end of projects, websites are launched, evaluated too early and then left and expertise is lost because the team was temporary, but resources could be allocated differently. Wellcome are taking a holistic approach to bring together the Wellcome Library and Wellcome Collection under one banner in a single domain model and to shift from a projects model to a product model. The team includes the necessary IT expertise and also a user researcher to help grow a team understanding of user needs. Key aspects of practice that have transformed work are

- Contact with users and moving to a more user-centric design

- Frequency of testing with users

- Recording and sharing the results of user research

User research matters because it

- Means needs are better understood

- Helps agile working as teams get immediate feedback and can shift direction accordingly

- Increases visibility of users

- Increases engagement with the website

Challenges include

- Recruiting neurodiverse and minority groups

- Recruitment logistics, e.g. finding the right people at the right time

- Balancing larger research studies with week-to-week design testing

- Time

Advice for getting started

- Grow user research skills from within

- Set aside time and talk to users regularly

- Shift project-based research to the beginning and middle phases

Karen ended by asking how should the sector recruit for future tech leadership and digital roles and make itself more appealing to people with tech skills?

Life before and beyond the ‘absolute unit’.

Kate Arnold-Foster and Guy Baxter (University of Reading) talked about how building digital strategy into their work led to the success of the Museum of English Rural Life’s (MERL) Twitter account and their #digiRDG project. Before their Twitter success, MERL thought they were under recognised and under used and felt that digital engagement would raise their profile and cut some of the hard work of attracting visitors. They discovered by trial and error that one person taking control was a better way of managing a Twitter account than sharing the duty of posting around the staff. They undertook some user research to understand how the new rural generation were using digital technologies and they obtained Arts Council funding. The #digiRDG project took a broad approach to digital culture and used agile techniques and regular digital content meetings to bring rigour to work. There is now also a following on Instagram and they have moved into 3D scanning and 3D printing. Not all staff had digital skills but had to stretch themselves. Kate and Guy felt it was important to focus on the conversation between themselves and their users, on the conversation between the museum, library and archive at Reading University, and on the conversation between the digital and the physical.

The wobbly stool: same goals, new roles

Joanna Finnegan (National Library of Ireland) described digital preservation as a three-legged stool, with a balance of technology, organisation and resources, and outlined how the National Library of Ireland has balanced these elements in managing the impact of the digital shift on collecting practices. She said that policies need to include collecting digital content and to recognise that “digital is different”. It was found that co-locating collection and technical staff was helpful. The resources which are most difficult to obtain and keep are staff. Demand for IT skills in Ireland is very high, as it is a large exporter of software. It was found that starting with technology can be a barrier, especially for small organisations, whereas digital preservation is much more than a technological issue. Joanna said that the important element is people and the ability to build relationships with creators and users. There is a need to work with these at an earlier stage than when collecting physical materials. For born digital collections, establishing relationships with donors is important. There is a need to be more proactive in building relationships with creators and users. The digital collections need to reflect diverse aspects of Irish life, as archiving the .ie domain is not part of Irish legal deposit regulations. Joanna summarised the relationship between physical and digital archiving, saying the goals are the same but the roles are different.

Questions to the panel

The panel was asked about planning. MERL had policies and procedures, but not everything was planned. Wellcome have shortened their planning time frame, looking three years ahead rather than ten. Co-operation between the GLAM sector and Google, as well as other large social media organisations, was discussed. It was felt that this would have to come at a governmental level, but that the main challenge is the one-way relationship of giving away content without learning anything about the usage or engagement. By using social media tools it is possible to engage with a huge audience for free. There was a question about what to deprioritise in order to achieve the digital shift. At the National Library of Ireland everybody kept on doing what they were already doing. MERL prioritised employing someone from outside the sector who had a real understanding of social media.

Keynote: Digital scholarship: Intersection, automation and scholarly social machines David de Roure, University of Oxford

David De Roure discussed the role of digital scholarship in research, sharing stories of his journeys into the evolving knowledge infrastructure. He defined digital scholarship in terms of the balance between people and computers, with more computers leading to distributed computation, more people leading to social networks, but lots of both resulting in digital scholarship and, eventually, to automation and machine learning. David first talked about social machines, where “people at scale meet computation at scale or the crowd meets the cloud”. His example, Galaxy Zoo, was a citizen science project where people helped classify large numbers of galaxies. It has now grown into the Zooniverse platform where anyone can build a citizen science project. Whereas one model of citizen science involves people doing independent work without talking to each other, in the case of Galaxy Zoo there was interaction between contributors which led to new discoveries. Galaxy Zoo also introduced machine learning, where contributors could assist the galaxy-classifying robot to improve. Reproducibility was covered next. Researchers need to keep records of how data has been processed, for purposes of reproducibility. David described the myExperiment project for sharing workflows, which led to Research Objects, which aims to improve reuse and reproducibility of research by supporting the publication of data, code and other resources and enriching them with any information required to make the research reusable and reproducible. Another social machine, MIREX (Music Information Retrieval Evaluation eXchange) brings the music information retrieval community together to improve the analysis of musical features. This is non-consumptive research, where a code is run over an archive without extracting content, meaning it can run over copyrighted material. It was used to analyse data in the SALAMI project (Structural Analysis of Large Amounts of Music Information) which applies computational approaches to the large volume of digital recorded music now available, in order to develop an infrastructure for conducting research in music structural analysis. David talked about new and emerging forms of data, such as tracking data, satellite imagery, social media data and data gathered by other online interactions, e.g. the internet of things, and also about found data, which is a side effect of other research and can cause tension with the established Social Science practice of carefully designed data collection. He said that understanding the processes that create the data is crucial in understanding the data. There is also sometimes an accidental assembly of processes, for instance if devices autocorrect text and accidently jump onto a different social machine. There are huge reproducibility issues with these data, for example it would be hard to reproduce a piece of research using the same Twitter data. Data is increasing massively in scale and the digital is interacting with the human (e.g. in social media) and with the physical (e.g. the Internet of things). The Living with Machines project, previously mentioned by Liz Jolly, was given as an example of the work of the Alan Turing Institute, which brings together Humanities and Data Science. Among the data-driven approaches it has used are experiments conducted though hackathons or datathons and machine-learning. A takeaway message was that “machines are users too”. David’s final story was about a project to build an AI based on Ada Lovelace’s ideas about the possibility of programming music with Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine. It would be possible to take a historical figure, study what they wrote and create an AI for them. The conclusion of the keynote was that we need to experiment. We have all the pieces of the future but haven’t figured out how to put them together yet.

Enabling digital scholarship

Jane Stevenson (Jisc) chaired this panel session focusing on how digital scholarship is facilitating and supporting innovative research.

Shaping the market: Developing scalable, researcher-oriented TDM services

Mike Furlough (HathiTrust) and John Walsh (HathiTrust Research Center) talked about text and data mining (TDM) services in the context of US copyright laws. They explained the HaithiTrust is fully funded by over 150 members. It builds the collection, preserves it and makes it accessible but also does other work such as investigating copyright status, collection management, e.g. linking print accessioning and deaccessioning to digital preservation, and work around TDM. The collection is predominantly books, with about half in English. The use is restricted with only about two fifths open for public reading. The collection is generally representative of North American libraries and is hosted at the University of Michigan, though some services and activities are hosted elsewhere. The members share expertise in order to do more with the collection. The HathiTrust Research Center was set up with the aim of developing scholarship in ways that haven’t been used before. The idea for developing the Center originated in part from the ruling that non-consumptive use was to be considered fair use in US law, though this is complicated by licences and it is important to be careful about how analysis is carried out on the in-copyright material. Services provided by the HTRC include:

- Extracted features – downloadable datasets of page level metadata and word counts, that can be used for topic modelling, linguistic analysis, among other things. They are not suitable for the novice user

- Web based algorithms for text analysis, which are more suitable for novice users.

Outreach and training are also provided. An example of research enabled by HaithiTrust was an analysis of 104,000 novels, which found that as gender equality gradually increased over time, the number of female characters and proportion of female authors decreased. Two important issues were raised. One is that research questions are not limited to individual collections, but span content that comes from different sources or aggregators. Questions of copyright can be confusing with content from licensed resources. For ECRs and new researchers, there are only limited training resources to help. Secondly, data from multiple sources will be provided in different forms, so it is necessary to do data cleaning. This adds to the need for training. Mike and John ended by asking how best to provide infrastructure and support and whether partnerships might be the answer.

Living with ‘Living with Machines’

Mia Ridge (British Library) discussed some early lessons learnt from working on the “Living with Machines” project, a 5 year partnership between the BL and the Alan Turing Institute to develop data science methods to ask historical questions using digitised collections at scale. The project brings together historians and data scientists and also invites the public to join the process. It makes methods, tools and code available for others to use. It is enhancing the BL data holdings, e.g. by disambiguating place names. The project is also asking how the work with the collections can be integrated into teaching data science and is trying to help politicians understand that the GLAM sector can do innovative digital work. The BL hopes to incorporate data science into its events programme. Challenges have been:

- Copyright – balancing openness with rights

- Expense of working at terabyte scale

- Challenges around workflows and ingest

- Sharing openly and early without gazumping people’s research

- Competing goals and deadlines at the BL

- Thinking about both scale and complexity at the same time

- Integrating crowdsourcing with academic processes and explaining academic processes to the public

- Bottlenecks that arise from having to wait for expertise

- Aligning ideas about whether to make code from scratch

- Access in the secure environment

Early research outcomes have been shared and the team skills have increased.

Providers, partners, pioneers: the development and diversification of digital scholarship services within Research Libraries and the potential for cross-sector collaboration

Matt Greenhill (RLUK) presented the results of a digital scholarship survey, published earlier this year and explored the role of the research library in delivering digital scholarship services. Some of the findings covered were:

- Defining digital scholarship is challenging, especially identifying what it means in practice for a research library, but 78% of organisations did have a definition, which was often aligned with their strategy. As it is a fluid term, lots of activities were encompassed in the survey.

- For activities surrounding the collection, respondents were confident and proficient. In more technical and specialist areas the proficiency was emerging and these activities were less likely to occur within the library.

- There is a mixed economy of support and the library is just one of the places researchers may go for support, though this situation appears to be changing.

- Many libraries are involved in digital scholarship initiatives, many of which originate from academics. But this can mean it is reactive in its services.

- Many libraries are looking to move from the role of service provider to active, costed partner, in order to have more of a voice throughout the process and to work in a more sustainable way.

- There are implications for the ways that libraries are structured. 11 libraries now have dedicated digital teams. These can ease communication, providing a single point of contact. New roles have been developed or rescoped. Dedicated spaces are also being created, providing physical and intellectual space for creation and collaboration.

- Activities are now increasingly being driven by overarching strategy.

- In the shift from analogue library to mixed digital and analogue economy, there is a two-way relationship between digital scholarship and digital collections in the library. The increasing volume of digital collections is opening a wider range of opportunities for researchers and this in turn is highlighting the role of the library as a digital repository.

- The increase in born digital collections brings challenges, such as the need for automated processes and secure access.

- The Library has the potential to be an active broker between multiple groups. It can provide spaces and be a catalyst for collaboration. It can act as a shop window for the institution, a place for experimentation and an incubator for collaboration.

- There is potential for cross-sector collaboration, e.g. between public libraries and universities around digital skills and scholarship, and also for collaboration in the international sphere, which RLUK is exploring.

Questions to the panel

The panel debated whether the term ‘digital’ creates an artificial division. It was thought that in terms of advocacy and because it is quite new, it can be a helpful term, but it depends on the audience. The term ‘digital humanities’ may eventually disappear, but for now it has a lot of utility. There was some discussion about the introduction of bias when there are sources missing in large aggregations and about how to represent “negative metadata”. It was thought that the structure of the library within the institution and whether it is conjoined with IT Services may have a bearing on the success of efforts to create partnerships. Some people thought that having a dedicated digital team helped. One museum/archive has made their collections data open access so they have their own dataset to use for demonstration and training. They run a library carpentry session for researchers.

Blockchain: the future for collections?

The final panel session, chaired by Matt Greenhall (RLUK) explored how blockchain technology could be used in the cultural sector.

ARCHANGEL – Trusted archives of digital public records

Alex Green (The National Archives) reported on research carried out in collaboration with the University of Surrey and the Open Data Institute on the potential of blockchain to underscore trust in digital records. He explained that digital files may be altered by archivists for legitimate reasons, e.g. conversion of the file format for presentation purposes, but users need to know that the file is a genuine copy of the original and not maliciously altered. The research project, which ended in June, used blockchain technology to prove that no changes had been made to a record, or that any changes made were legitimate. Checksums, which are like unique fingerprints for a file consisting of letters and numbers, and other metadata were written to a blockchain. Multiple organisations then held a copy of the contents. The distributed network meant that consensus could be achieved because nothing written to a blockchain can be changed. The chain that links blocks together is made of the checksum of the previous block and a new checksum, which is generated based on the content and on the old checksum. For files that were legitimately altered, it was thought that checksums of the software used to change the file could be added to the blockchain. Alex emphasised that collaboration between archives is key to the successful use of blockchain.

Blockchain and the museum: turning digital fragmentation into social value

Frances Liddell (University of Manchester) drew on her collaborative PhD project with National Museums Liverpool in order to address the question of what blockchain can do for the GLAM sector and how we might turn digital fragmentation, found on blockchain technology, into social value. Ideas of being collaborative, visitor-focused, inclusive and ethical and cultivating social value were all incorporated into the project. Frances discussed the concept of collective ownership, which is less about physical ownership and more about co-operation, with the focus is on guardianship rather than cultural property. Collective ownership in the digital domain has an extra layer of complexity because it challenges the notion of authenticity as well as the idea of the museum acting as keeper or authority over items in its collections. Frances linked this idea to the Open Museum movement, which releases digitised collections online under creative commons licences. Frances explained the qualities of blockchain, using the example of the blockchain game CryptoKitties, and how blockchain can prove the authenticity of a document. Blockchain can be used when selling digital art, as the consumer knows that the art’s authenticity can be proven. Shared ownership can also be tracked on blockchain and a sense of social community can be formed. Frances concluded that blockchain is not a fully formed solution to issues of ownership online, but can help build collective ownership and shared authority between museum and audiences.

Introducing Project Arbour, a digitisation and cultural blockchain catalogue access project

Geoff Blissett (Max Communications) discussed a collaborative project with Centre for Scientific Archives and Cognizant to digitise catalogues of the manuscript papers of scientists and make them cross-searchable, adding blockchain technology for verification purposes. A prototype application was built and testing with user groups has begun, which has been effective in identifying potential risks and problems and quantifying how useful it will be. They are currently in the process of developing use cases. Like the other panel speakers, Geoff briefly explained the principles of blockchain and said that the blockchain element helps with transparency and giving users confidence in the veracity of the material. It provides traceability as it is possible to see where any changes are made and it provides an audit trail, showing where an item has come from and the steps it has made on its journey, so it can help with identifying human errors, or questions or disputes about ownership of a document or copyright. Geoff outlined the workflow: The collection holders provide the material, which is digitised and digitally preserved by Max Communications. The package, including metadata and PDFs, is then passed to Cogizant who put it into a blockchain and load it into the cloud.

Questions to the panel

The panel were asked about the environmental considerations of blockchain, in terms of energy usage. It was explained that a private blockchain takes less energy. There were concerns that blockchain technology could become obsolescent quite quickly. Whilst acknowledging the dangers, it was generally thought that blockchain is here to stay but is in its infancy. The community is still trying to see if it works and can make a difference.

Videos of some of the keynotes and audio recordings and slides of some of the panel session papers are available.

Conference delegates were left with plenty of food for thought (and plenty of time to think about it on the way home, as trains from Birmingham New Street were delayed by flooding disruption). Take home messages included the importance of collaboration, as partner institutions can achieve more together. Collaboration also needs to take place with stakeholders and with end-users, and good communication is key to collaboration. The GLAM profession needs to become more representative of communities and to be inclusive and welcoming. There are challenging questions to tackle of authenticity, bias and ownership in the digital world. We need to learn new digital skills, take some action and embrace the digital shift.